Strong Abs, Healthy Back

By Shy Sayar

As a yoga therapist, one of the most common questions that people ask me is how to get great, strong abs. Even some of the elite, world-class athletes that I have trained have asked me how to get especially the lower abs strong and toned.

On the other hand, everyone also always asks how to heal and prevent back pain, and Theraputic Yoga For Hips and Back is routinely the most popular of all my videos on Yoga Download, month after month. So I have decided to write and share this article with you, because it is important to understand that the two are intrinsically related: strengthening the abdominal muscles, and especially the lower fibers of the abs in conjunction with the pelvic floor and the adductor muscles of the inner thighs, is the perfect complement to a therapeutic practice for the hips and back. The problem is that most people, including even many teachers and practitioners, have no idea how to isolate the lower ab muscles from the perennially tight psoas muscles, resulting in ever more tightness in the hips and vulnerability in the lower back, in spite of the best intentions. The good news is that there are simple solutions - once we understand the deep dynamics of the hips, abs and back.

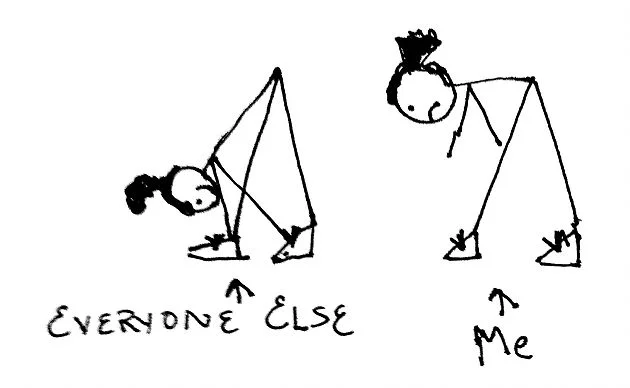

The psoas muscles, which are the primary hip flexors, bring the torso and thighs towards one another. If you imagine the torso coming towards the thighs or the thighs towards the torso, you might notice that from the outside this looks like any classic abdominal exercise. However, there is no guarantee that bringing the torso and thighs towards one another will efficiently tone the abs, since it is all too easy to overuse the psoas muscles and bypass the all-important stability muscle fibers in the lower abs. What most people call ab work is predominantly just hip flexion - and nobody needs tighter hips.

Moreover, since the psoas muscles wrap around the spine and attach to the lumbar, they directly affect the stability and posture of the lower back. Therefore, a lot of so-called ab work ends up mostly tightening the lower back as well as the hips, and can eventually lead to injury and pain. Emotionally, the hip-flexing psoas muscles are the first responders to fight-or-flight signals, as flexing the hips is the first action both in closing off the front of the torso to protect the vital organs, as well as in preparing to lunge - whether in order to attack or to flee. In our modern world, where we are mostly removed from the food chain and do not normally have to escape or fight carnivorous predators, this relationship between the psoas muscles and the fight-or-flight mechanism has been mostly sublimated into traumatically stored tension in response to any and all perceived danger, whether physical or emotional. So, again - nobody needs tighter hips.

The well-intentioned but sadly harmful message that so many of us get from a very young age, namely to suck our gut in and keep it in, actually makes affairs worse. Imagine what would happen if you walked around all day with your elbows flexed and your fists held tightly by the shoulders in a classic muscle-man pose; would this result in strong and supple biceps, or weak and exhausted ones? The same is doubly true of the abs: a truly strong muscle must be able to fully extend, as well as fully flex. Strength without mobility is merely tightness, and flexibility without stability is merely weakness. What we want is truly strong and supple muscles, throughout the body in general, and in the abdominal muscles in particular.

Thankfully, there is a simple action that is the initial key to healing the hips and back and gaining true access to the abs. It is an action that, by nature, we should all be doing easily and perfectly, virtually all the time: deep, diaphragmatic breathing. Of course, due to the very same physical and emotional tensions at the root of the problem, nearly nobody actually breaths perfectly well all the time, to say the least. In order to begin to heal the breath, and hence the abs, hips and back, we would do well to understand the structure of the respiratory diaphragm.

The respiratory diaphragm is a dome-shaped mass of muscle and tendon fibers that separates the hydraulic (liquid system) abdominal cavity in the lower torso from the pneumatic (gas system) thoracic cavity in the upper torso. It basically connects the bottom of the ribcage to the diaphragm's own central tendon at the top of its dome. In order to inhale, we engage the diaphragm muscles to pull its central tendon down towards the abdominal cavity, which results in expanding the lungs. Since the lungs are connected to the atmosphere in a pneumatic, air-pressure system through the air canal, nostrils and mouth, the expansion of the lungs creates an air-pressure difference between the lungs and the atmosphere. In turn, the lower pressure in the lungs, relatively to the atmosphere, causes air from the atmosphere to rush into the lungs. You have literally never "taken" a breath. All we do is engage the respiratory diaphragm, and mother earth virtually breathes into us. Talk about opening to grace.

Yet, tension in the abs from holding them in and from emotional trauma restricts the proper descent of the central tendon of the respiratory diaphram. In lieu of the respiratory diaphragm descending, we must then overuse auxiliary respiratory muscles in the chest, upper back, shoulders and neck. Muscles such as the intercostals between the ribs and the upper trapezius that connect the back of the head and neck to the collarbones were designed to assist inhalation, especially under the pressure of aerobic activity, but not to bear the brunt of respiratory effort. As a result, so many of us end up with tightness and pain in the shoulders and neck. So, if you'd like to heal or help prevent shoulder and neck pain, ultimately you must also learn how to breath more efficiently with your diaphragm.

This is why all of my abwork programs start with deep belly breathing. Strengthening the abs and healing the hips and back are deeply related, and both find their roots in diaphragmatic breathing. Then you can learn how to recruit the mula bandha principle at the pelvic floor, as well as the hip adductors in the inner thighs, to isolate the lower fibers of the abdominal muscles from the psoas and begin to gain real freedom in the hips and back, as well as perfect functional power in the core.

The technique depends on going slowly enough to notice whether you are able to retain perfect stability and stillness throughout the body as you perform minute and precise supine leg lifts, it also includes many, many levels of challenge, and it is crucially important to stick to the level that still allows you to keep perfect core stability, in order to prevent the psoas from taking over and making matters worse. When it is virtually effortless at one level, it is time to move to the next. Once you are able to lift and lower straight legs from a supine position with perfect stillness in the rest of the body, you will have perfect functional core stability. Then yoga (as well as Pilates, dance and athletics) will be much safer for your back, and more likely to do good than harm in the long run.

Lastly, you can learn how to expand the sides and the back of the waist during deep diaphragmatic breathing, so that you can keep the lower abs and pelvic floor lifted while still breathing deeply. As I learned in my university education in music and vocal performance, any excellent opera singer knows that breathing "into the kidneys" allows for the best breath support for vocal projection. During more actively challenging yoga asana practices, it is also the way to get the best of all worlds: deep breathing, uncompromising core stability, and perfect relaxation in the neck and shoulders. This is why I emphasize, in strength building classes such as Slow Flow and Twists and Backbends, lifting the lower belly and the pelvic floor. This action allows us to open the hips and breathe deeply into the sides and the back of the waist, while keeping the upper torso and neck surrendered. From a more esoteric, energetic perspective, this is also the first step towards uddyana bandha. We can thus also begin to learn how to use the lift in the lower belly and pelvic floor like an energetic magnet for the vital energy of respiration, drawing prana into the body's center of gravity and power at the base of the torso.

While it takes time and practice, dedication and patience, when we truly gain an experiential understanding of the dynamic relationships between our hips, abs and back, as well as our breath and vital energy, we open the door to a lifetime of fitness and wellness in body and mind that translates into great freedom and joy, even unto old age.